|

|

Background to June 12

An understanding to the events that led to the proclamation on Philippine Independence on 12 June 1898, the convention at Barasoain that started on 15 September 1898, and the culmination of the republican efforts that led to the inauguration of the Philippine Republic on 23 January 1899 - could not be advanced without highlighting the social, ideological, philosophical and political underpinnings that defined the contours of the events and determined the course of the Philippine revolution. In all of these events, masons and Masonic ideas played significant roles that determined the leadership, identified the mass membership, and delineated the ideas that inspired the events that happened from Kawit to Barasoain in the seven months preceding the proclamation of the Republic on 23 January 1899.

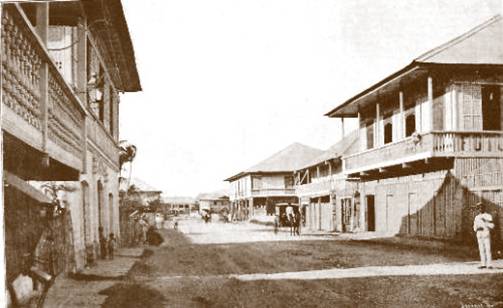

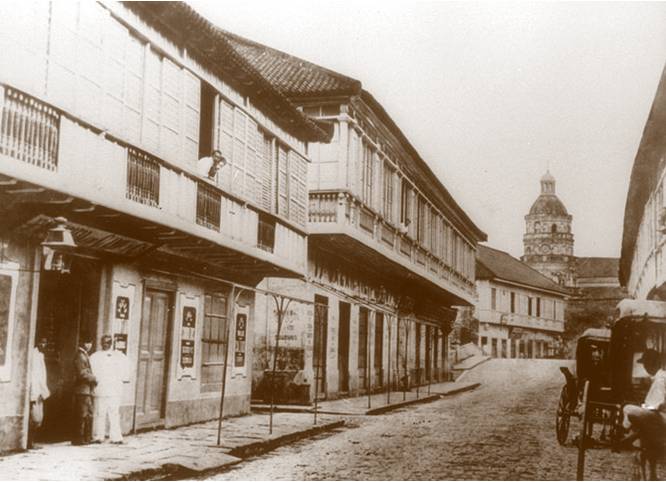

The social context that characterized the leadership and mass membership of the revolutionary movement was defined by the nineteenth century social divisions based on race, class, ethnic origin, place of birth, political power, cultural and linguistic background of people, and social status of the different groups of people in the country during the period. A social pyramid, with the ruling class on top of it, characterized such social arrangement. The pyramid could also very well represent the demographic composition of these social divisions, with the ruling elite that constituted the numerically most insignificant, but politically and socially most prominent ones occupying the topmost position. The base of the pyramid, of course, was constituted by the mass of local population – politically powerless, socially marginalized and economically impoverished by the social and economic dispensation of the colonial order. Topmost of these groups were the peninsulares, literally, those Spaniards who were born in the (Iberian) peninsula in Spain. Called Españoles Europeos, the Hispanic heritage of this group was most pronounced in their culture, language, and ethnic composition. Majority of the peninsulares were members of the semi-permanent, transient population of civil, military and religious officials whose tour of duty in the Philippines was but a small part of their careers based in Spain. These officials would at times be assigned to the archipelago and would bring with them their peninsular families, staying in the country temporarily, with the desire to go back to Spain at the end of their respective appointments. But some peninsulares either by choice or forced by circumstances would opt to stay in the archipelago, and would be considered as permanent residents. Examples of these are the friar members of the religious orders whose terms of office would at times entail a lifelong tenure in the parishes, or some Spanish families whose business and agrarian interests necessitated them to stay and adopt the Philippines as their secondary home. Nonetheless, most of the peninsulares would still consider Spain as their mother country, and would maintain strong ties with the colonial motherland. Immediately below the peninsulares were the insulares, or those of pure Spanish parentage, but were born and raised in the archipelago. At times, some insulares would have had no experience of living in any other country outside of the Philippines. Having the Philippines as their birthplace would distinguish them from (sometimes discriminate them against), the peninsulares. Called Españoles Filipinos (or simply Filipinos), the insulares would be viewed with suspicion by the peninsulares because of some questions of loyalty and affinity to the motherland. The insulares may be Spanish in culture and language, but most of them had not even gone to Spain in their lifetime, and would ascribe to the Philippines as their motherland. Despite being economically and financially well endowed as their peninsular counterparts, the insulares would somehow be treated politically as somebody below the peninsulares, and therefore would be considered as politically powerless compared to the peninsulares. The long years of Spanish colonialism already paved the way for the development of class of people with mixed parentage. Called the mestizos (literally, mixed blood), the group would comprise not only the offspring of Spanish and local union, but also all children of mixed parentage, including the numerically more significant Chinese population. The mestizo therefore will further be subdivided into two subgroups: the mestizo Españoles, or those born to the union of native and Spanish parents; and the mestizo Sangleyes, or those born to the union of native and Chinese parents. Since demographically the mestizo Sangleyes would constitute the demographic majority amongst the mixed blood population, the term mestizo, without the qualifier, would at times be generically referred to the mestizo Sangleyes. The mestizo class during the nineteenth century would occupy a significant role in the social and economic transformation of the country, but would still not be acknowledged as having the potential for political leadership by the peninsulares. Having access to the local economy that was beginning to take the shape of an institutionalized system of commodity exchange, the mestizos gained some economic leverage with the establishment of cash crop production ventures and export and import businesses in local trade. Some mestizos, therefore, became as financially and economically prominent as their peninsular or insular counterparts. This afforded some of them to send their children to the best tutors in the countryside, and even to higher education in Manila and Europe – exposing a new generation of mestizo population to cultural Hispanization and westernization. With the implementation of the 1863 universal education decree that opened the doors of academic institutions to those willing and could afford the costs of advanced education – the mestizos took advantage of the opportunities of cultural Hispanization by way of the educational system. This transformed the class into one of the most Hispanized and economically prominent sectors of society. But just like their insular counterparts, their having been born and raised in the archipelago and at the same time have native blood in them would render some limitations to their political stature in the colonial dispensation. Despite their wealth and Hispanized culture, therefore, the mestizos were as politically marginalized as their insular brethren. Below these groups were the members of the local population, collectively known as indios, a misnomer referring to the colonial possession as being part of India, a colonial legacy that reflected the fixation to the conquest of India, that resulted in condition similar to the mislabeling of native-American communities. While racially unified as having indigenous parentage and being born and raised in the archipelago, the indios were separated and could further be classified along two distinct class lines. The indios principales (sometimes called principalia, the principal individuals and families of the local population) were considered as colonial intermediaries of the local population and were given limited power in local governance. Some of them became cabezas (heads) of village communities who assisted the colonial administration with their religious, bureaucratic and military campaigns at proselytization and colonial subjugation. Although racially indigenous, some children of indio principalia families also experienced a certain level of cultural Hispanization and financial status. But just like their insular and mestizo counterparts, their access to political authority was severely limited only to the positions in the local governance that became the sole avenue for their political participation in the colonial process. Below all of these were the other groups of pure blooded subjects of indigenous population called the indios naturales. Technically, even the principalia belong to the naturales category, but because of differences in income, social status and cultural Hispanization, the principales were often referred as distinct and separate from the indios naturales. The naturales were economically and politically marginalized, and were least Hispanized among all the groups in the colonial society. These conditions separated them from their principalia counterparts. The other groups of significant mention were the pure blooded Chinese migrants who made the Philippines their second home, called Chinos or Sangleyes. Some of the Sangleyes were converted to Catholicism (called Sangleyes cristianos) and therefore were allowed to receive the sacraments of marriage (at times, with the local women), creating a new class of mestizos discussed above. Some Sangleyes remained non-Christians (and were called Sangleyes infieles) and were subjected to the uncertainties of the shifting policies of the colonial administration regarding their stay in the country. But because of mutual racial antagonism and mistrust felt between the Spanish and Chinese population, the Chinese were often discriminated in the colonial society. It was only because they were the progenitors of the emerging mestizo Sangley class that were becoming prominent in economy and society that the pure blooded Sangley were able to lessen the pejorative regard that they would receive from the colonial establishment. Read more |